Lincoln's Cooper Union Speech Sesquicentennial

Yesterday, Abraham Lincoln's speech at Cooper Union celebrated its 150th anniversary. Although not as well known as the Gettysburg Address, his 2nd Inaugural, or even the Lincoln-Douglass debates, the speech delivered at Manhattan's Cooper Union Institute may, in the big picture, be more important.

The speech took place during the 1860 presidential election. Democrats accused antislavery Republicans, such as Lincoln, radicalism. Senator Stephen Douglass, the likely Democratic nominee, supported the concept of “popular sovereignty," which argued that the Constitution did not authorize the U.S. Congress to stop slavery from spreading into territories and that the residents of the territories should decide the slavery issue for themselves.

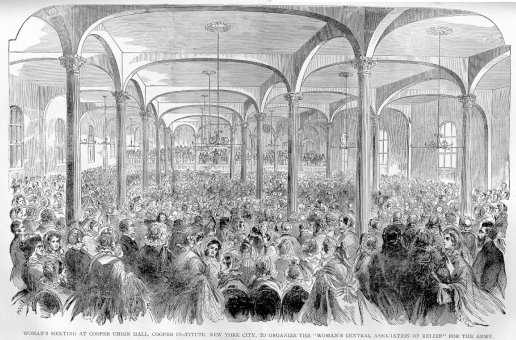

Eastern Republicans eagerly searched for a Western candidates with broad public appeal to take on Douglass. According to Lincoln scholar, Harold Holzer, the Young Men’s Central Republican Union invited several Western politicians to speak at Cooper Union--a lecture series that essentially served as auditions for the Republican nomination. And that is how, on February 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln found himself in a basement auditorium facing a curious audience.

The Illinois "rail splitter" made, to put it mildly, an unimpressive first Impression. One observer described him as

“an awkward specimen indeed” with “one of the legs of his trousers...up about two inches above his shoe; his hair was disheveled & stuck out like rooster’s feathers; his arms much longer than his sleeves.” While he looked pretty bad, Lincoln sounded even worse. His voice was described as “thin” and “squeaky," which, according to the New York Herald had a “frequent tendency to dwindle into a sharp & unpleasant sound.”

Nevertheless, ninety minutes later, Lincoln found himself on the receiving end of thunderous applause and cheers. The speech was a triumph. The New York Tribune praised it as “one of the most convincing political arguments ever made in this city” and the Cooper Union address eventually became known as “the speech that made Abraham Lincoln president.”

So what did Lincoln say in this speech that garnered such a strong reaction? The genius conceit is that much of the oration addressed a single sentence favoring popular sovereignty uttered by rival Douglass in an 1859 speech in Columbus, Ohio. That line read: “Our fathers, when they framed the government under which we live, understood this question just as well, and even better, than we do now.” According to Douglass: the Founders created a nation divided into free and slave states and each state could decide the slavery issue for itself. Under the Constitution, Douglass maintained, the federal government could not do anything about it. Douglass stressed the need to defer to those sacred founders.

Lincoln boldly agreed with Douglass on one point--those who created our government did understand slavery issues better than the people of 1860. Harold Holzer, in his book, Lincoln at Cooper Union describes Lincoln's speech research and preparation in addressing that issue. Lincoln, huddled alone in the Springfield State Library, with no research assistants, scholars, or clerical staff to aid him, pored over legislative histories and congressional debates. He found that, of the 39 signers of the U.S. Constitution, 21 voted in favor of federal regulation of slavery. Fifteen others expressed sympathy with the sentiment of ending slavery expansion. Therefore, Lincoln contended that 36 out of the 39 “fathers” who “framed the government under which we live” supported Lincoln’s position. The Republican added: “This shows that, in their understanding, [nothing] in the Constitution, properly forbade Congress to prohibit slavery in the federal territory; else their oath to support the Constitution would have constrained them to oppose the prohibition.” He continues this methodical and logical argument building for 20 paragraphs, all the while constructing a meticulous and clever case against slavery expansion.

Lincoln brings passion to the end of his oration where he declares that “groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong, [is] vain as the search for a man who should be neither a living man nor a dead man…let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

One hundred and fifty years ago, the Cooper Union speech bolstered the political prospects of both Lincoln and his party. Its success was due primarily to clever persuasion strategies and exhaustive research. But there’s more to it than that. The speech also has been called the “right makes might” speech because of that final passage. However, that nickname ignores another critical term in that coda. Faith. “Let us have faith that right makes might and in that faith, let us…dare to do our duty.” Lincoln invested months studying dusty books and gathering his evidence because he had faith in what the Constitution means--a movement toward more freedom and equality. And in crafting a speech that reflected that meaning, Lincoln also reconstituted that meaning for his generation and for ours. So, one lesson that we can take away from Lincoln at Cooper Union is that, especially in difficult times, we cannot lose faith in the Constitution. Even in times of cynicism, polarization, apathy, and dysfunction, when, as Lincoln said, too many leaders are “groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong,” we must remember the trajectory of our Constitution is always a forward one.

Labels: Abraham Lincoln, Cooper Union Speech

<> Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home