To celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. this year, I had my students read his Holt Street Church speech at the start of the Montgomery bus boycott. The speech can be found

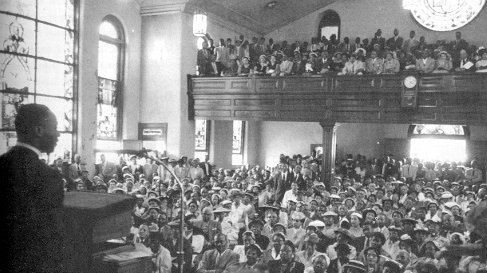

here. It seems like students get inundated with "I Have a Dream" on this day each year, even in non-communication classes. So I went with this speech from early in his career as a civil rights activist when King was just emerging as the powerful voice of the civil rights movement. King, then minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist church, was only 26 years old when he was elected chair of the Montgomery Improvement Association and tapped to deliver this speech.

King starts the speech vaguely innocuous, stating that the crowd was there to "apply [their] citizenship" and to "get the situation corrected." In the second paragraph, he defines the problem that needs correcting--the intimidation and humiliation of blacks on the city buses--but doesn't use the word "segregation." The problem had existed for some time but became urgent with the arrest of Rosa Parks for her now legendary refusal to surrender her seat to a white person.

How does the arrest of a single African-American suddenly render bus segregation an urgent problem? Because of the quality of Parks's character. King describes her as "one of the finest citizens in Montgomery" and, using his trademark parallelism, adds that “nobody can doubt the boundless outreach of her integrity....nobody can doubt the height of her character....nobody can doubt the depth of her Christian commitment and devotion to the teachings of Jesus.” For King, if such an exemplary Christian person could be thrown off a bus and arrested, then the system in Montgomery and elsewhere must be broken. This passage also introduces the theme of Christianity, which plays an important role throughout the speech.

Starting in paragraph 5, King makes the case justifying the right to protest. Here, he addresses the speech to a national audience for the first time, addressing the general public apprehension about black activism. In seeking to connect with a wide audience and relieve their fears, King grounds the right to protest in Christianity and American democracy. He contrasts the American right to protest with what would occur "behind the iron curtains of a Communistic nation"--a timely and patriotic cold war shot that would resonate well in 1955. In paragraph 7, King reaffirms the Christian and democratic themes by explicitly connecting the protestors with the U.S. Supreme Court, justice, God, and Jesus. My students seemed to like this passage in particular:

"And we are not wrong, we are not wrong in what we are doing. If we are wrong, then the Supreme Court of this Nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a Utopian dreamer and never came down to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie."

In paragraph 8, he explains that Christian love must include the concept of justice. Justice, King argued, is "love in application" and is needed for "correcting that which would work against love." This neatly ties back to the beginning of the speech and King's stated purpose of correcting a problem. The minister assures African-Americans that good Christians can participate in a bus boycott--and other acts of civil rights protest.

The speech is a great example of a creative yet tidy argument aimed at multiple audiences. It also shows King as a gifted speechwriter early in his career, years before the triumph of the March on Washington. In fact, a few phrases appear in both the Holt Street speech and the 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech--his use of Amos 5:24 ("until justice runs down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream") and the phrase "long night of captivity." The bus boycott wouldn't end for another year and only after a U.S. Supreme Court decision, but this address surely inspired and reassured blacks at the critical beginning of the Montgomery protest.

From a teaching standpoint, what was great was listening to my students identify numerous passages that they felt still resonated with a contemporary audience and with the students themselves. King's meshing of Christianity and justice should hold a special appeal for students whose Catholic college supports a mission of social justice. Without any prompting from me, they found the speech's message useful and relevant to an example of oppression in their own community--the gay-bashing cartoon that recently appeared in

The Observer, the Notre Dame-Saint Mary's student newspaper. The students' use of King's words to challenge and condemn the hateful cartoon is exactly the type of thoughtful and engaged reaction that this day should be all about,

Labels: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.